© Conner Family Trust, San Francisco

© Conner Family Trust, San Francisco

© Conner Family Trust, San Francisco

© Conner Family Trust, San Francisco

© Conner Family Trust, San Francisco

© Conner Family Trust, San Francisco

© Conner Family Trust, San Francisco

THE WHITE ROSE

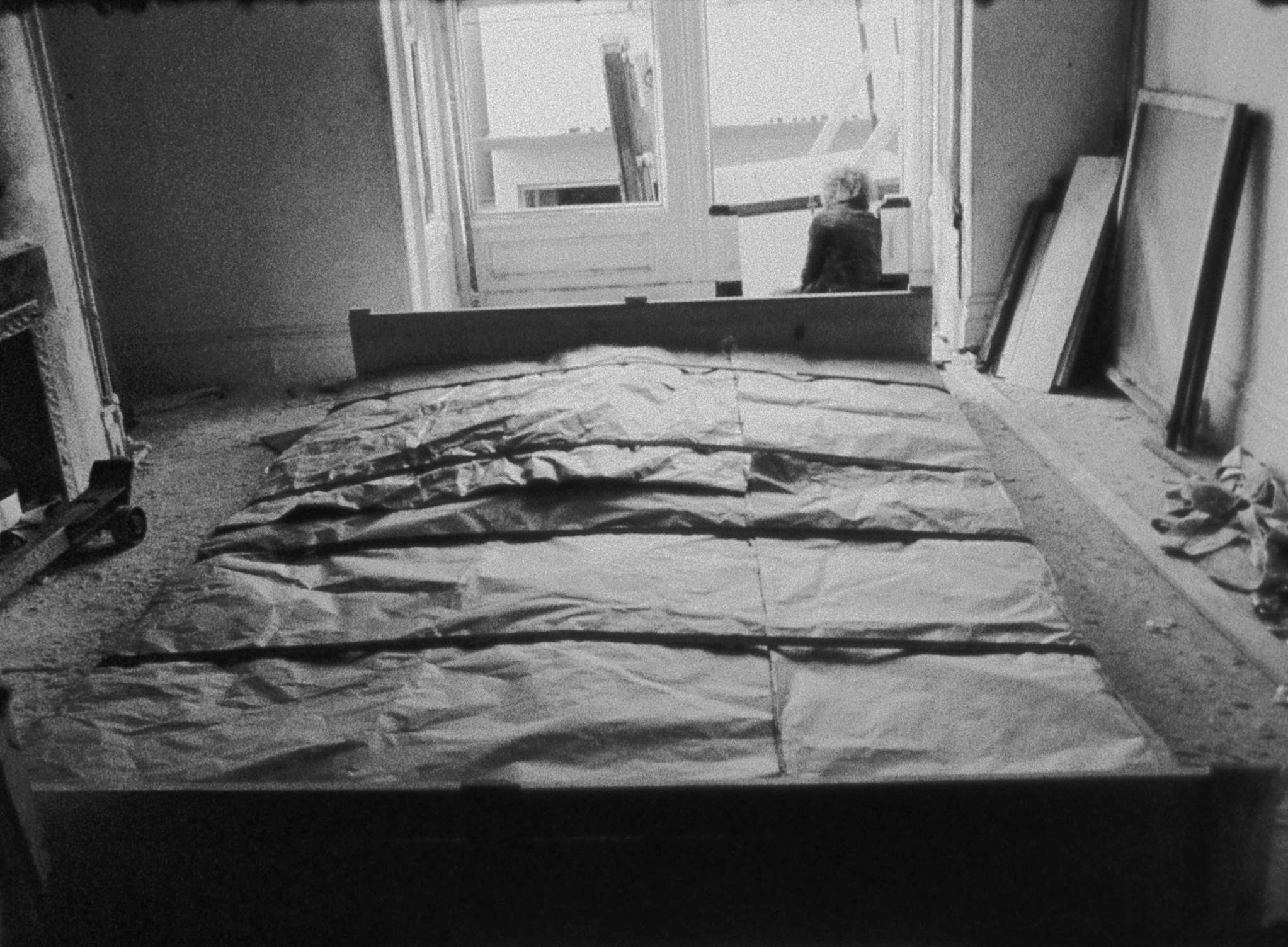

1967, 16mm, b&w/sound, 7min.

Jay De Feo started painting THE WHITE ROSE in 1957. When the unfinished painting was removed eight years later it weighed over 2300 pounds.

"The images selected and the order constructed become a formal mystic service. We see the altar, the penitence, the cross, the investiture, the descent, and finally, the mourning. The men in garments from Bekins seem to draw strength from touching the surface. The respect they render the painting appears as worship."

– Camille Cook

"... a fine, brief, tongue-in-cheek 'documentary' of a huge painting being removed from an artist's studio, carried onto a Bekin's moving van with a combination of cold efficiency and all the lugubrious solemnity of a state funeral. It has remarkable timing and pace, and an 'artless' style which can only come from a deep sense of what the art is all about."

– Thomas Albright, Rolling Stone

BACK TO FILMOGRAPHY

Shortly after coming to San Francisco, Conner formed what he christened the “Rat Bastard Society.” Conner told the curator Peter Boswell that the name was fitting for “people who were making things with the detritus of society, who themselves were ostracized or alienated from full involvement with society.”

A naked woman performs a striptease as fireworks burst. Mickey Mouse, looking off-screen left, shoots goo from one of his eyes while Minnie scowls. The end of the reel rolls. Then a close-up of the girl, breast to butt, with a bright lollipop of lights above her. A diagram of egg-like teeth appears with "No brushing" shown upside-down. Another reel starts. The upright lady dances, more fireworks. Reel end. She's totally naked, and we can see all the sweet spots. Another reel mark, with a countdown. Soldiers march to war. Reel mark. Breasts, hand, and waist. Reel mark. Breasts and hair. Reel mark. The boys plant the flag at Iwo Jima. Breasts. Reel mark. Soldiers. Fireworks. Ray Charles, singing "What'd I Say" on the soundtrack, moans.

A Bruce Conner film might be constructed from a dozen or a hundred instances—shards, jolts, figments—of déjà vu. Though it may employ fewer: Marilyn Times Five (68-73), where an iconic handful of b&w nudie tableaus are gracefully looped back on themselves as though refracted through a peep-booth's two-way mirror (just a recumbent Monroe lookalike, a bottle of Coke, and thou). These images, scavenged from home movies, newsreels, stag films, Defense Department footage, educational shorts, and TV commercials, are summoned forth from our collective consciousness, and beckon us down that irrationalist primrose pathos into their subterranean lairs. If the specter of the Sixties continues to haunt the imagination, as an unraveled utopia of ruined shrines, forsaken promises, and impossible desires, then Bruce Conner is the era's truest documentarian, as well as its shadow DJ.