SELECTED PRESS

Bruce Conner, Bellas Artes Projects, Manila, 24 February – 24 May

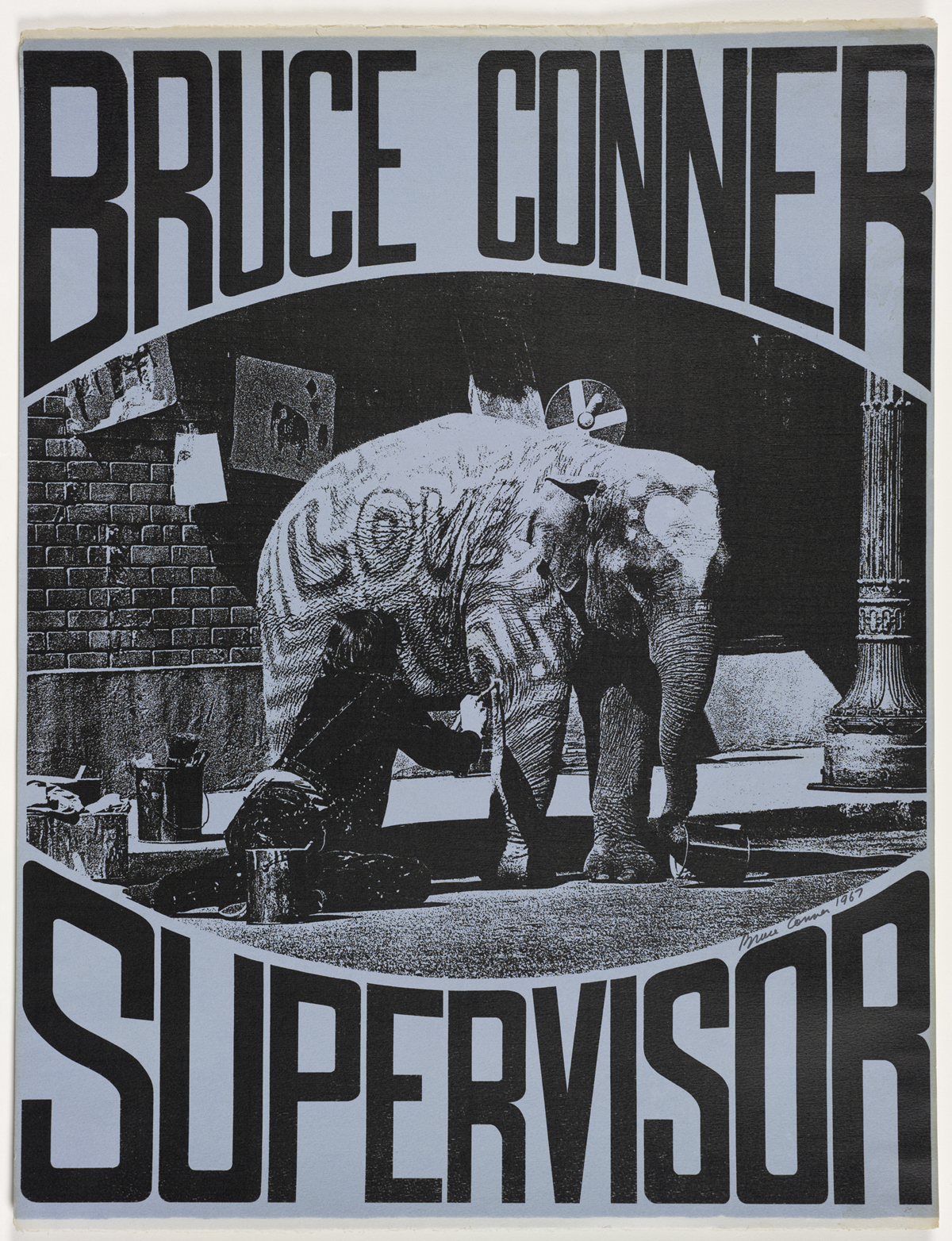

Affiliated with California’s neosurrealist assemblage scene from the 1950s onwards but a mystic-minded outrider even there, Bruce Conner was determinedly elusive in life. He announced his own death twice, officially renounced art in 1999 and earlier operated under aliases including Emily Feather, BOMBHEAD and the Dennis Hopper One Man Show. Conner was also, as his recent resurrection within the artworld reflects, something of a visionary.

If you missed the recent MOMA survey dedicated to the quicksilver Bay Area artist, who died in 2008, at the age of seventy-four, this show makes a fine introduction. A recently restored version of Conner’s 16-mm. film “Report,” from 1967—on view alongside the ingeniously irritating avant-girlie movie “Marilyn Times Five,” made in 1973—considers how a nation processes trauma, the magnetic appeal of conspiracy theories, and the slippery nature of time.

The Speed Art Museum presents BRUCE CONNER: FOREVER AND EVER, an exhibition of films and prints by Bruce Conner (1933–2008), an artist known for his innovations in film, assemblage, drawing, painting, photography, printmaking, and collage. Co-curated by Miranda Lash, Curator of Contemporary Art, and Dean Otto, Curator of Film, BRUCE CONNER: FOREVER AND EVER is the Speed’s first exhibition collaboration between its Contemporary Art and Film departments.

As 2017 winds down to a close, the Speed Art Museum will send the year out in style with its newest exhibition, BRUCE CONNER: FOREVER AND EVER. The exhibition — co-curated by the Speed’s curators of contemporary art and film, Miranda Lash and Dean Otto, respectively — covers the works of Bruce Conner, the late artist from McPherson, Kansas, who worked in photography, sculpture, printmaking, as well as film, and was known as the “father of the music video.” It marks the first collaboration between the Museum’s contemporary art and film departments.

Conner, Shaw, Pettibon, and Wojnarowicz burrow into moments in America’s recent past when the forces of darkness seemed ascendant. Conner’s reflections on the allure of nuclear annihilation during the Cold War, Shaw’s fascination with religious sects that resist the pull of modernity, Pettibon’s exploration of the rubble left by the failure of the 1960s utopian dreams, and Wojnarowicz’s evocation of the AIDS catastrophe of the 1980s all belong to a tradition of anxiety rooted in Apocalyptic thinking. But they also remind us of the ambiguity at the heart of the eschatological narrative.

Bruce Conner's ground-breaking first film A MOVIE (1958) will be extended until July 15th at 3 Duke Street, St James's.

Shortly after coming to San Francisco, Conner formed what he christened the “Rat Bastard Society.” Conner told the curator Peter Boswell that the name was fitting for “people who were making things with the detritus of society, who themselves were ostracized or alienated from full involvement with society.”

Bruce Conner's A MOVIE installation at Thomas Dane Gallery has been selected by The Guardian as one of the top five exhibitions of the week.

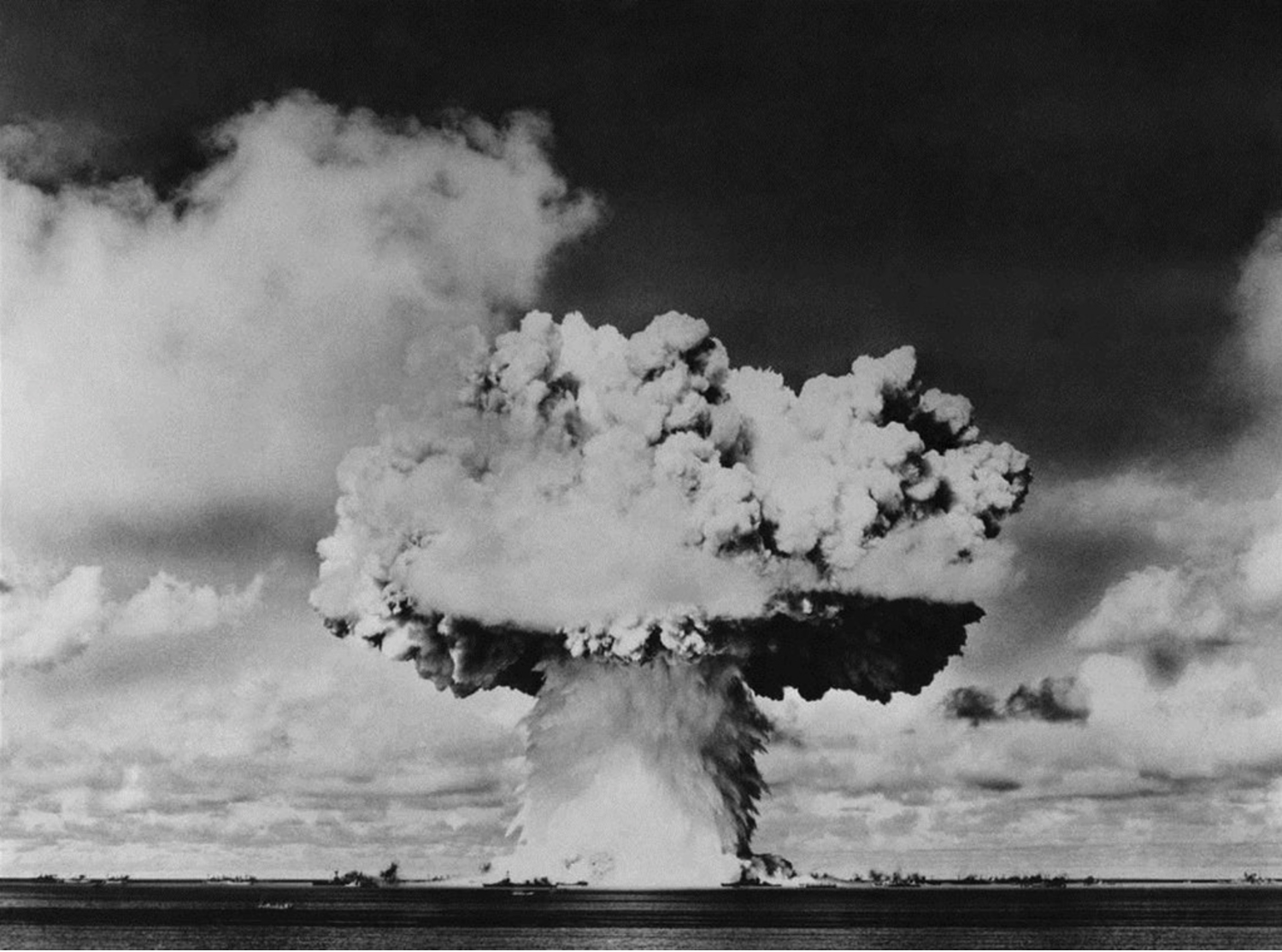

Bruce Conner’s Crossroads (1976), a film featuring 37 minutes of slow-motion atomic bomb explosions that recently appeared at the museum’s retrospective for the San Francisco–based artist and is also one of it's recent acquisitions.

The Mercury News ranks “Bruce Conner: It’s All True” at the San Francisco Museum of Modern the #1 museum show to see before it closes.

Seeing Bruce Conner's career survey, It's All True, at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art brought back to me the sense of urgency, relentlessness and wry confrontation that I experienced 16 years ago when I interviewed Conner, who died in 2008.

Two strong Bruce Conner exhibitions that might be missed in the shadow of the artist’s extraordinary retrospective at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (“It’s All True,” through Jan. 22) are being simultaneously presented at downtown galleries. Both shows are small, particularly in comparison to the massive SFMOMA affair, and both focus on aspects of Conner’s extensive graphic work.

Running from now until January 22, 2017, Bruce Conner’s posthumous exhibit at the SF MOMA, “It’s All True,” features work spanning the entirety of his 50-year career. Provocative but poignant, chaotic but contained, his art is a convoluted journey of self-discovery in a catalyzing Cold War era.

This is a still from Bruce Conner’s great 1976 art film called Crossroads, which is a collage of clips from the government’s own footage of the 1946 Bikini Atoll nuclear test. (See a clip here.) The piece is now showing in the exhibition called “Dreamlands: Immersive Cinema and Art, 1905–2016” at the Whitney Museum in New York, after also starring in the recent Conner survey at MoMA. An apocalyptic crossroads – how could I not run it on this particular morning in American history, where blowing things up seems the order of the day?

Senior & Shopmaker Gallery is presenting Bruce Conner’s, one-person exhibition of photo etchings, “Dennis Hopper One Man Show, 1971-73” till November 12, 2017.

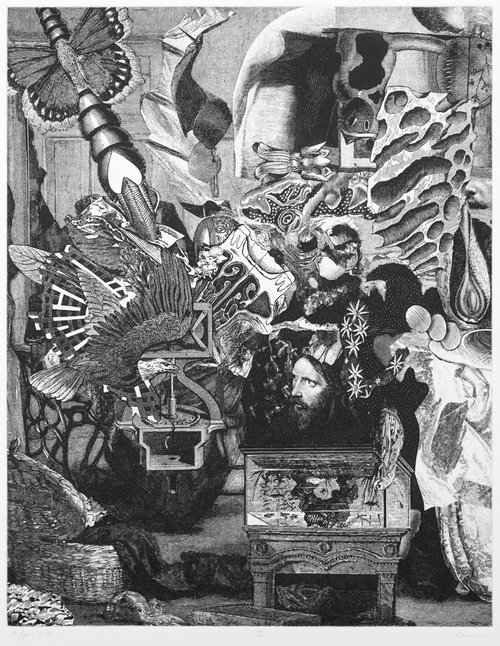

Acting simultaneously as artwork and as foil for a larger conceptual project, this series is considered by many to be among Conner’s major works. Conner’s collages depict a surreal, hallucinatory universe populated by images of flora and fauna, machine parts and disembodied figures.

Bruce Conner was such a quirky artist that reference books and museum guides sputter in their attempts to define him. He was “a master of the macabre” expressing “profound pessimism,” a “defiant Bay Area individualist.”

The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art is determined to uplift Conner’s stature with an authoritative new exhibit. It includes more than 200 works covering a 50-year career as a painter, collage creator, sculptor, filmmaker and art world prankster. Titled “It’s All True,” a riff on the many responses to Conner’s work, it runs through Jan. 22.

A retrospective has the ability to map the arc of an artist's career, its unifying and diverging themes, but it's unlikely that it's an artist's intention to have his or her life's work shown en masse. So does this mode of presentation enhance, skew or alter the perception of the work? That question arose recently when viewing Bruce Conner: It's All True,the first and certainly most multi-faceted, comprehensive survey of the prodigious 60-year output of this Bay Area iconoclast who, to paraphrase that old Sinatra standard, did it his way.

When MTV launched in 1981, David Byrne and Brian Eno commissioned a couple music videos that would become benchmarks for the medium. Like Byrne and Eno’s experimental music, both videos used only repurposed materials, including footage from old sales training and science education films. None of the appropriation was authorized. The music videos were never aired.

In an onstage conversation Wednesday, Oct. 26, at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, where Directors’ Circle donors were previewing “Bruce Conner: It’s All True,” it was emphasized that Conner, “the quintessential artist’s artist” by museum director Neal Benezra’s description, was a man of paradox.

If there was ever any doubt about who should be recognized as the greatest artist the Bay Area ever produced, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art has resolved the question definitively with its lovingly presented, sweeping analysis of the work of Bruce Conner. The exhibition “It’s All True,” opening Saturday, Oct. 29, comprises some 300 works and is accompanied by an authoritative, 384-page book. Together, show and catalog provide a detailed argument for the artist’s dominance in a range of media, from collage and assemblage, to independent film, to conceptual art.

Ask any art school student “Who is Bruce Conner?” and depending on their major, they’ll provide you with a vastly different answer: a) Bay Area conceptual artist; b) experimental filmmaker; c) that guy with all the inkblot drawings; or d) “Who?”

The correct answer is e) All of the above. And more.

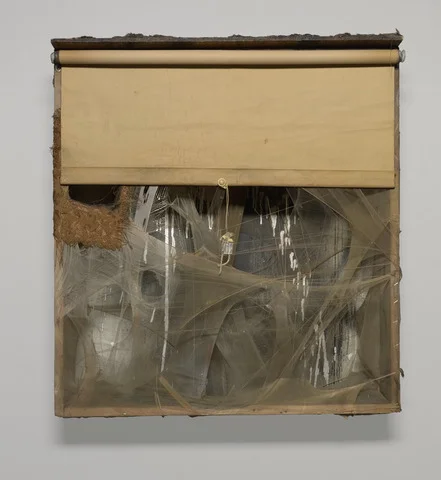

His tiny inkblot drawings are there. So are the huge tapestries populated with biblical figures and utterly strange heads. And so are his punk-rock photos, typewriter drawings, and the 1961 assemblage titled HUNK DING DONG JUNK YING YANK that incorporates everything from torn nylons to egg cartons and looks like a Pharaonic object meant to survive into the afterlife.

He made an art film about the Kennedy assassination and delicate, meditative paintings based on inkblots and autumn leaves. His haunting assemblages, like those of a viscerally rotting “COUCH” or a mutilated and gauze-shrouded “CHILD” bound in a high chair, hold an undimmed charge more than a half century after they were made. So do his photographs of San Francisco’s burgeoning punk rock scene of the 1970s and ’80s. Female nudes proliferate in his art. Mushroom clouds of nuclear bombs are forever blooming — one from the neck of a headless man in a collage.

It’s taken a long time for Bruce Conner (1933 – 2008), the polymath San Francisco artist who was a major force in the development of both found-object sculpture and experimental film in the United States, to be given a major retrospective. An iconoclastic innovator in multiple media, he spent five decades eluding definition, avoiding a signature style or association with any one movement. He was also a master of contradiction, creating challenging artworks that combine opposites such as sex and death, conceptuality and materiality, and spirituality and politics.

“WHAT A SHOW! WHAT A SHOW!” The reaction of the unseen, breathless, and elated MC at the end of Bruce Conner’s moving-image installation Three Screen Ray, 2006, is likely to be the exclamation of many a visitor exiting “Bruce Conner: It’s All True,” the revelatory retrospective of some 250 works currently installed at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (through October 2). In his half century of making art, Conner (1933–2008) embraced painting, sculpture, assemblage, collage, drawing, photography, performance, and movies—all (save, perforce, performance) generously represented at MoMA.