Dagny Janss and Bruce Conner

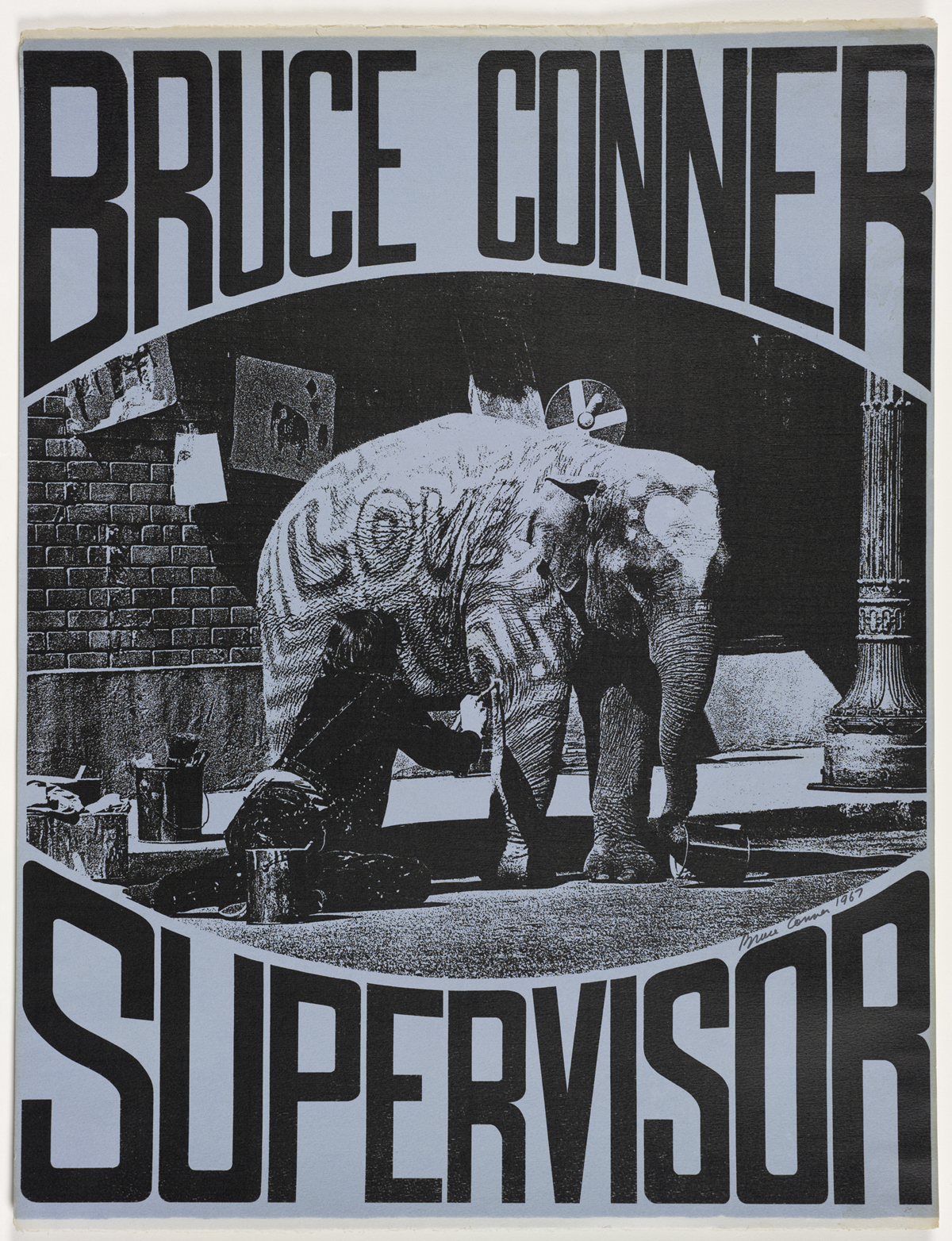

BRUCE CONNER for SUPERVISOR, 1967

Two color screen print

Collection San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Gift of Michael Kohn, © Conner Family Trust, San Francisco / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

BY SARAH HOTCHKISS

Ask any art school student “Who is Bruce Conner?” and depending on their major, they’ll provide you with a vastly different answer: a) Bay Area conceptual artist; b) experimental filmmaker; c) that guy with all the inkblot drawings; or d) “Who?”

The correct answer is e) All of the above. And more.

Conner’s prolific career, spanning the mid-1950s to his death in 2008, is now on view in SFMOMA’s mammoth retrospective It’s All True, opening Oct. 29. Over six decades, he worked in nearly every media available to artists of his generation, purposely defying both market forces and easy categorization. As soon as he gained recognition for a certain style (as was the case with his early assemblages), he had a tendency to abandon that style completely. He even “ended” his own art career by declaring himself dead on two separate occasions.

It’s All True often organizes Conner’s wide-ranging practice by material and subject matter (compare his otherworldly “angels” photograms with his black-and-white photos of San Francisco’s late ’70s punk scene), but it’s important to realize many of the works — collages, films and drawings — were made concurrently.

Nowhere is this more obvious than in the “Hecho in Mexico, 1961–62” gallery (look for the joyful light yellow walls), a room filled with works made while Conner and his wife Jean lived in the Juárez neighborhood of Mexico City. Sourcing everyday materials from his home, he covered items like shoes, a folding screen and a pillow with collaged paper, photographs and brightly colored paint. Projected in the center of these objects are two versions of the film Looking for Mushrooms, compilations of fuzzy colors, slow-motion fireworks and religious festival footage set to the Beatles’ “Tomorrow Never Knows” and Terry Riley’s “Poppy Nogood and the Phantom Band,” respectively.

By contrast, the rest of the exhibition is starkly monochromatic. But don’t confuse lack of color for a lack of complexity. A half-day spent in It’s All True — a time period made necessary by the 336 works on the exhibition’s image list — will take the viewer on an emotional journey from ecstatic, foot-tapping delight (whatever you do, do not miss BREAKAWAY, Conner’s 1966 film featuring Toni Basil singing and dancing in various states of undress) to silent, horrified awe (see his 1976 filmCROSSROADS, soaring aerial footage of atomic explosions paired with an original composition by Patrick Gleeson and Terry Riley).

It’s no accident that the two examples above are both films. Using stock educational footage, Hollywood B-roll and his own camerawork, Conner’s quick cuts and purposeful use of filmic conventions still mesmerize — nowhere more so than Three Screen Ray, a frenetic three-channel projection set to the tune of Ray Charles’ “What’d I Say.” It’s All True is interspersed with 10 of Conner’s film pieces. Make sure to watch them all.

It’s difficult to write about Conner’s practice in both a comprehensive and concise way, even eight years after his death. There’s just so much there there. A through-line in his career was a willingness — perhaps even a compulsion — to throw a playful wrench into art business as usual. A prime example: the room of intricate engraving collages made over the course of three decades. Through deft juxtapositions of found illustrations, Conner rendered these small-scale scenes surreal and hilarious. He tried to show the collages in 1967 under actor, filmmaker and photographer Dennis Hopper’s name, but — in a phrase that becomes familiar over the course of It’s All True — the “proposal was rejected.” Instead, he published three volumes of DENNIS HOPPER ONE MAN SHOW, etchings of his collaged etchings, with Crown Point Press in the early ’70s.

Conner’s willingness to mix fact with fiction is nicely summed up by the retrospective’s enigmatic title. It comes from a quote that opens the exhibition, a long list of conflicting descriptors for the artist’s work, summarized by his assertion that “it’s all true.” Conner embraced and encouraged his own difficult-to-pin-down-ness in way that’s inspiring in today’s competitive and reductive art market. In the multiple-choice, open-ended question of Bruce Conner’s fascinating and enduringly salient career, the answer is always: e) All of the above.