BY MATTHEW BIRO

It’s taken a long time for Bruce Conner (1933 – 2008), the polymath San Francisco artist who was a major force in the development of both found-object sculpture and experimental film in the United States, to be given a major retrospective. An iconoclastic innovator in multiple media, he spent five decades eluding definition, avoiding a signature style or association with any one movement. He was also a master of contradiction, creating challenging artworks that combine opposites such as sex and death, conceptuality and materiality, and spirituality and politics.

That this is his first large-scale exhibition in nearly sixteen years is thus not surprising—although it makes the show even more significant. Comprising more than 250 works in approximately ten different media, it is organized both chronologically and thematically, a strategy that allows visitors to appreciate the power and depth of Conner’s engagement with different subjects and materials without reducing the peripatetic nature of his vision. Running the gamut from painting, drawing, collage, photography, printmaking, film, and video to conceptual art and installation, It’s All True reveals Conner to be a simultaneous critic and admirer of American culture, a melancholy and ironic bricoleur who embraced both high and low, sacred and profane.

The earliest works on view are thickly painted, quasi-monochromatic paintings made of oil and other substances on Masonite. Gouged with a stylus, they expand the vocabulary of Abstract Expressionism through an exploration of materiality and primitivist mark-making, while also divulging Conner’s interest in geology and paleontology before leaving the Midwest in 1957. Works made in San Francisco immediately thereafter disclose a rapid growth in the artist’s tendency to incorporate heterogeneous materials with burgeoning accumulations of found objects and magazine fragments, bringing representational content into dialogue with painterly abstraction.

Conner’s breakthrough into assemblage in 1958 was inseparable from the city of San Francisco, whose thrift shops and dilapidated Victorian neighborhoods he mined for castoff objects and detritus evocative of an earlier, more sentimental moment. His innovative “RATBASTARDs” and related works from 1958 and 1959 resemble handbags or dreamcatchers. Consisting of picture or window frames swathed with nylon stockings (or pendulous sacks made out of the same fetishistic garment), they bulge with fabric, fur, twine, nails, costume jewelry, photographs, and printed papers: abandoned accessories of anonymous lives given new dynamism as parts of secular reliquaries. This work betrays a gothic sensibility due to its dark tonalities, worn surfaces, and quasi-Victorian iconography of lace, beads, feathers, flowers, and materials that constrain the body. Significantly, despite Conner’s appropriation of sexist pinup imagery and his obsession with femmes fatales from Hollywood’s Golden Age, the substances that comprise these assemblages are mostly associated with female identity. And this tension—between objectifying women and identifying with them—is characteristic of Conner’s wholehearted embrace of paradox.

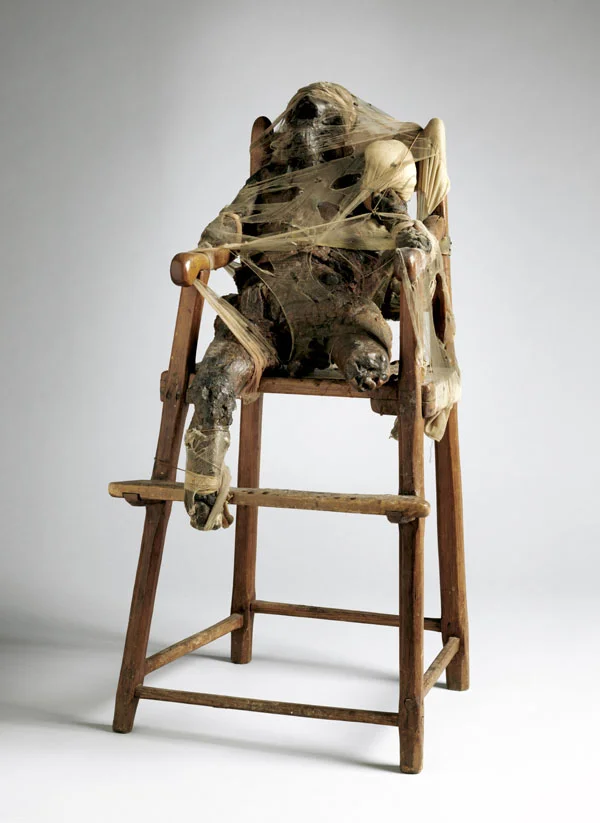

Many of Conner’s “BLACK WAX SCULPTURES,” made between 1959 and 1963, repeat the same motif—a half-mummified body bound to a supporting structure—and they evoke spiritual issues surrounding death and the afterlife while simultaneously pointing to more concrete political concerns having to do with capital punishment, abortion, nuclear Armageddon, and war. CHILD (1959) depicts a grimacing figure composed of wax, cloth, and metal, lashed to a scavenged wooden high chair; it was created to protest the impending execution of Caryl Chessman, sent to the gas chamber in 1960 for heinous, but non-murderous, crimes. Superimposing the nurturing of an infant with the execution of a man, Conner’s assemblage blends political activism with an evocation of moral crisis. There is a palpable sense of spiritual loss here, an atmosphere that suggests thatU.S. society was becoming increasingly bloodthirsty and that traditional religious belief systems no longer held sway.

In 1964, Conner abandoned assemblage, increasingly devoting himself to monochromatic, abstract drawings. (Living in Mexico City between 1961 and 1962—where scavengable objects were less plentiful and greater access to psilocybin mushrooms allowed Conner to experiment with hallucinogens more frequently—may also have influenced the artist’s turn to trippy graphics.) Felt marker drawings, begun in 1963, reveal an interest in process and trance-like mental states produced by repetitive actions. Composed of dense crosshatchings surrounding simple geometric shapes like circles, these all-over compositions are hypnotizing and obsessive. Many of them take the form of mandalas, religious emblems used in meditation practices. In 1974, Conner began making pen and ink drawings, gradually occluding white paper with rich fields of black. Created through a slow process of eliminating all positive forms, some are entirely opaque, while others retain minuscule points of light and evoke stars in a night sky. Finally, in 1975, Conner invented an intricate technique of inkblot drawing, which he continued until he died, sometimes releasing these works under pseudonyms after he pretended to retire from art in 1999. The symmetrical motifs that populate these quasi-automatic drawings were created by making a progression of marks and then folding them while wet along a central axis. Simultaneously vegetal, insectile, and hieroglyphic, these arrays of Rorschachian forms suggest a process in which conscious choice interacts with worldly contingency. And like the artist’s other graphic experiments, the inkblot drawings mix opposites—dark with light, material with immaterial, conscious with unconscious, and individual with collective.

Conner was probably best known as an experimental filmmaker, and this side of his creative practice is carefully highlighted. The show begins with a continuously repeating screening of his twelve-minute masterpiece A MOVIE (1958), an assemblage of more than 180 pieces of found footage—much of which shows races, chases, and disasters—set to an orchestral score. Appropriated from a wealth of sources including newsreels, travelogues, stag films, countdown leaders, B movies, and industrial films, the film uses classic Hollywood cutting techniques such as motion and eye-line matching to create connections between unrelated shots. In one sequence, a U-Boat captain spies a lingerie-clad beauty through his periscope and fires his torpedoes in barely-sublimated response; in another, a nuclear bomb explodes producing a tidal wave causing a series of surfers, boats, and water skiers to capsize. A focus on elemental imagery—earth, air, fire, and water—gives AMOVIE a mythological, prescientific resonance, and careful shot selection and rapid-fire editing allow the filmmaker to present the world as protean matter in a continuous state of flux. Paradoxically, A MOVIE seems to acknowledge a postmodern condition in which a flood of simulacra appears to supplant the real, while at the same time suggesting that a still-perceptible conflict of primordial forces exists beneath the play of representations.

In general, Conner’s films raise compelling questions about humanity’s place in a world where destructive forces impinge upon the individual from both within and without. CROSSROADS (1976), is another tour de force, a thirty-seven-minute elegy to the fundamental loss of innocence that accompanied our entry into the Atomic Age. Editing together declassified government footage of Baker, the underwater nuclear bomb test at Bikini Atoll on July 25, 1946, the film uses a minimalist score to help convey a horrifying impression of an apocalyptic Cold War sublime. With shots lasting from a few seconds to more than six minutes and unfolding at a variety of different speeds, the mushroom cloud explosion repeats multiple times, cycling like a pornographic film loop from which the viewer cannot look away. As geysers of vaporized water erupt from the ocean and overtake warships anchored at ground zero, we are asked to contemplate the particular Rubicon that the world crossed over that day.