On Bruce Conner, Jim Shaw, Raymond Pettibon, and David Wojnarowicz

The Apocalypse has long been a staple of American film, pulp fiction, popular culture, and high art and literature. Lately it has also been looming large in our political consciousness. From a presidential adviser who is convinced we have entered the fourth and final “turning” in human history to charges by environmentalists that our withdrawal from the Paris climate accord may push global climate change to a tipping point, the Trump era has so far been a time of dark forebodings and doomsday rumblings. At the same time, the art world has been facing its own version of Armageddon with the threatened demise of federal arts funding, the uncertain future of the NEA, and renewed attacks on the First Amendment.

Artists are among our most vocal Cassandras. On the environmental front, Alexis Rockman and Walton Ford play with scenarios of devolution and eco disaster, while Diana Thater, Jane and Louise Wilson, and Richard Misrach explore post-apocalyptic landscapes created in the aftermath of nuclear and chemical accidents. One of the most striking works in this year’s Whitney Biennial was The Island, a video by Tuan Andrew Nguyen, who uses the real-life setting of a former Vietnamese refugee camp to stage a dystopic narrative about the last man and woman on earth.

Major art museums, not usually seen as bastions of doomsday thinking, have also tapped into the mood. Consider the titles of four recent and upcoming retrospectives: Jim Shaw’s “The End Is Here” at the New Museum; Bruce Conner’s “It’s All True,” organized by the San Francisco Museum of Art; David Wojnarowicz’s upcoming Whitney retrospective, “History Keeps Me Awake at Night”; and Raymond Pettibon’s recent New Museum show, “A Pen of All Work.” (The latter’s reference is a bit more obscure; it’s a line spoken by Satan in Lord Byron’s apocalyptic poem, “The Vision of Judgment.”)

The subjects of these retrospectives emerged from various backgrounds and frame their concerns in different ways, but all share a talent for unearthing the creepy things crawling beneath the shiny surface of American culture. They also share a debt, through their youthful exposure to religion, to the tradition of eschatology, or the study of Last Things. The canonical text of the Apocalypse is the Book of Revelation, which recounts the perfidy of Satan, the final, grand battle between the forces of good and evil, and the end of the world as we know it. This mythology has burrowed deep into the modern psyche and provides a language for thinking about our own more secular crises and catastrophes. For these four artists Apocalypse becomes a way to deal with our darkest fears.

Bruce Conner, who died in 2008, was born in Kansas but hit his stride in California, where he spanned the beat, hippie, and punk eras. While he rejected his parents’ more mainstream Protestantism, he was fascinated with the revival meetings he attended as a child, and the sense of magic and mystery he imbibed there remained with him throughout his life. In a 1986 interview printed in a 1999 Walker Art Center exhibition catalogue, he told British curator Peter Boswell, “It seems to me that, within religious contexts there are certain ways of talking about experience that don’t exist otherwise.” Discussing his particular interests, he added, “Religion carries on a dialogue of relating life to death and the forces that control the world, your life and you. These are mysteries to everyone.”

This fascination lay behind a body of work that encompassed experimental film, assemblage, photography, collage, and painting, and drew on influences as diverse as Christianity, Tantra, Native American spirituality, and gnosticism. The connecting thread is a vision of the interdependence of life and death, matter and spirit, catastrophe and rapture. Conner’s works explore the uncanny beauty of destruction, the American romance with violence and mayhem, and the convergence of sacred and secular roads to ecstasy.

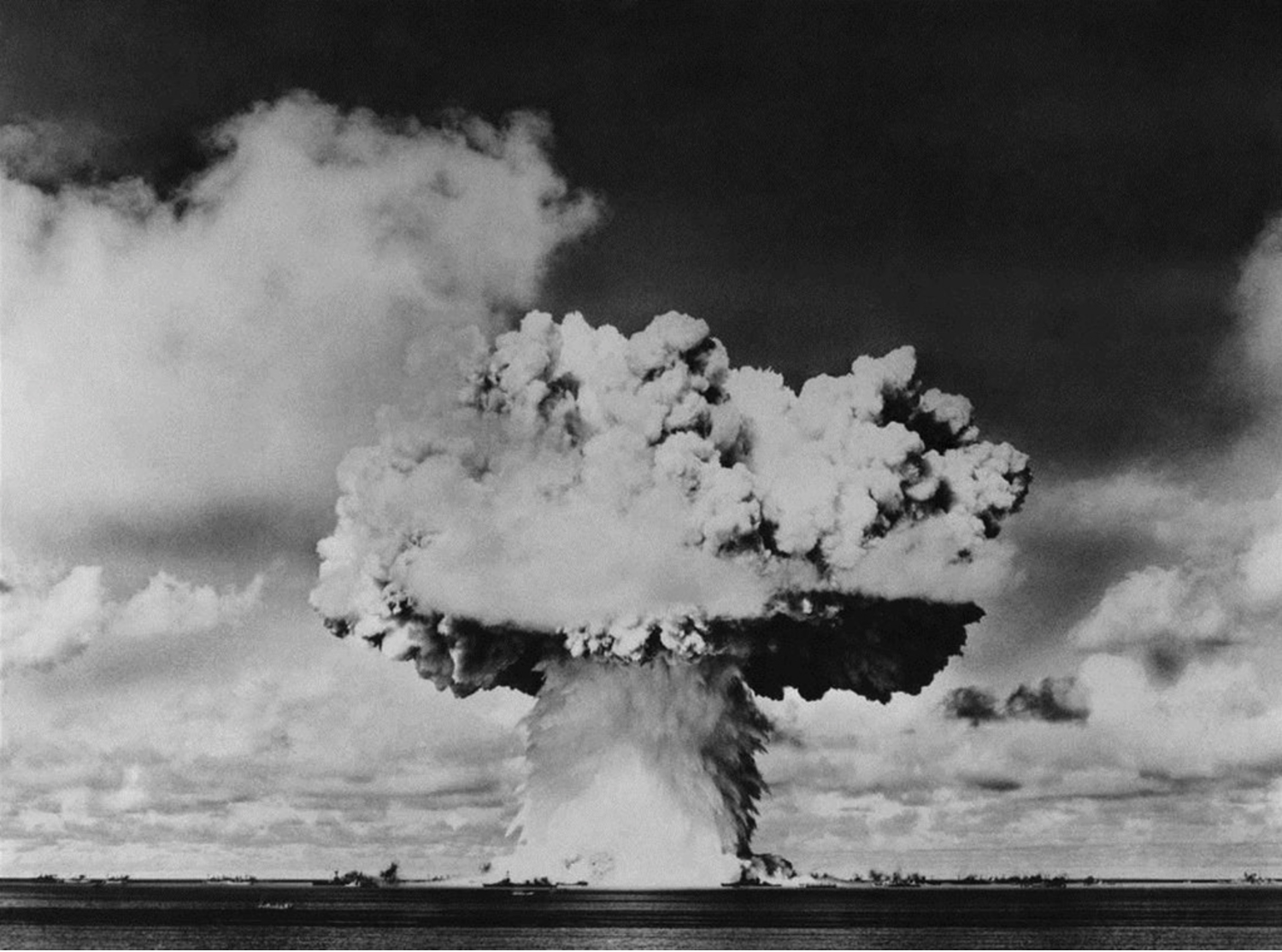

One of Conner’s recurring themes was the atomic bomb, whose potential for the ultimate annihilation of the human race hung over Cold War America like a persistent fog. It appears in collages, drawings, and films—most dramatically in Crossroads (1976), a 37-minute film comprising archival footage of previously classified documentation of the July 25, 1946, atomic test at the Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands.

The atomic bomb explosion examined in Crossroads, which New York audiences got a second chance to view in the Whitney Museum’s recent exhibition “Dreamlands,” was copiously documented by the U.S. Government with 700 cameras and 500 camera operators, and Conner provides sequence after sequence of the same blossoming cloud from different angles. Patrick Gleeson scored the first half of the film with sounds that simulate the explosion. A 16-track recording of Terry Riley performing on an electronic organ accompanies the second half. It is as undeniably beautiful as it is unsettling; as the bomb slowly detonates over and over to Riley’s meditative music, it presents an image of what has been called the nuclear sublime. Thus, Crossroads serves, even more than Conner’s equally provocative meditations on the Kennedy assassination, violent crime, and natural catastrophe as a paean to the American romance with death and the possibility of global obliteration.

Shaw has made Apocalypse one of the primary subjects of his work. Over the last 40 years, he has pursued a multifaceted career that includes autobiographical narratives, murals, performances, and installations, as well as an archive of America’s esoteric mythologies and beliefs that serve as source materials for Shaw, and which he exhibits under the title “The Hidden World.”

Shaw recoiled from a conventional Episcopalian upbringing in the small town of Midland, Michigan. He fell in with a group of so-called rebellious Catholics, including artist Mike Kelley, with whom he founded the cult band Destroy All Monsters; he later enrolled in art school at CalArts. Shaw locates America’s soul at the intersection of popular culture, commercial kitsch, and eccentric spirituality, drawing a line between Hollywood and American messianic sects and cults. The connection comes easily to him, as a former special-effects designer for such offbeat Hollywood films as Earth Girls Are Easy (1988), Nightmare on Elm Street 4: The Dream Master (1990), and The Abyss (1989).

At the New Museum, “The Hidden World” was represented by such finds as the books of Zecharia Sitchin, a Russian-American author who maintained that human life on earth was the product of an alien invasion; the Universal World Church, a show-biz mega church that, during the 1950s, was situated under what they called a “glory cloud” that emitted smoke by day and fire by night; and publications by Jack Chick, an evangelical comic book artist and publisher who espoused the belief that the Catholic Church is behind Islam, the Jehovah’s Witnesses, Communism, and the Holocaust.

Shaw’s own work includes paintings inspired by the best-selling Christian “Left Behind” novels written by Tim LaHaye and Jerry B. Jenkins. These books update the Book of Revelation, relating the contemporary struggles of those “left behind” to deal with the Great Tribulations after believers are raptured out of homes, cars, and airplanes. Shaw’s homage consists of allegorical murals painted over monumental theatrical backdrops that capitalize on the associative link between fundamentalist Rapture and the American working class left behind by globalization. Shaw alters the backdrops with overlays of images from pop culture, politics, and ’50s-era advertising, turning modern figures like Tom DeLay, Pat Robertson, Ayn Rand, and Ronald Reagan into the four horsemen of the Apocalypse, and the leaders of the G7 countries into the Beast with Seven Heads.

Raymond Pettibon, born in 1957, is Shaw’s rough contemporary and, like Shaw, experienced the post-1960s hangover that descended after the Age of Aquarius disintegrated into the nightmares of Watergate, Charles Manson, and the Symbionese Liberation Army. Over the objections of his Catholic father, Pettibon was raised as a Christian Scientist, a sect with strong connections to the Book of Revelation. It is tempting to read that sect’s metaphysical idealism as the original target of Pettibon’s restless, demolition-prone imagination.

His work reflects an anarchic spirit expressed in collage-like drawings and wall works that mingle references to high and low culture. The drawings consist of reassembled bits of Victorian poetry, reconfigured slogans, and thought fragments scrawled over cartoonish images of surfers, mushroom clouds, superheroes, political figures, baseball players, and gruesome crime scenes. In Pettibon’s leveling process, Gumby meets Socrates, and Saturday-morning cartoons mingle with quotations from Marcel Proust, William Blake, Samuel Beckett, and the Bible. At first glance, the work appears deliberately adolescent, like the tapestry of sketches, scrawls, and fanzine pages one might find on a teenager’s bedroom wall. But, in fact, Pettibon is grappling with profound issues.

Chief among these are questions about the false promises of politics, religion, art, drugs, sex, and rock ’n’ roll. There are frequent references to Christianity, as in a 1985 drawing whose text reads: “One mustn’t pray too hard, or God will think you are dissatisfied with life, and scoop you up.” The Christian deity often appears, as curator Ulrich Loock has noted, in humiliating circumstances. In a 1988 drawing, an image of Christ is accompanied by the taunt “have you cured cancer?” Pettibon’s installation for the 2004 Whitney Biennial (and on view in his recent drawings exhibition) turns from the Creator to created, providing an inventory of creation from jellyfish to humans to supernovas, overwritten with the scrawled question “how can we have projected onto him lights so dim and powers so unsteady?”

Through the 1980s Pettibon turned frequently to the motif of Charles Manson. The notorious murder of actress Sharon Tate and four others by Manson’s “family” of misfits occurred in 1969, when Pettibon was 12. He recalls a neighbor remarking that Manson was the personification of evil. Reportedly, Manson was inspired by the Biblical Apocalypse as reinterpreted through the Beatles’ song “Helter Skelter.” In Pettibon’s hands, Manson becomes a figure of the anti-Christ, at once a scapegoat and media distraction from the other evils of the time and the specter of middle America’s fears of the era’s social and sexual upheavals.

Other apocalyptic themes include fires, swords, and mushroom clouds that later morph into representations of the shock and awe of the Iraq War. Even Pettibon’s iconic drawings of surfers dwarfed by oncoming waves are, as he notes, his version of the sublime. Like a giant sponge indiscriminately soaking up the flotsam of society’s conscious and subconscious, Pettibon spits out unexpected juxtapositions that reflect on humanity’s fallen condition and dire future with an arresting combination of existential dread and gallows humor.

Addressing a very different and more intimate threat was David Wojnarowicz, who died 25 years ago. Arguably the foremost arts spokesperson of the AIDS era, Wojnarowicz’s art and writings chronicled a difficult childhood and adolescence, including his abusive alcoholic father and his life as a homeless gay hustler in New York City. Immersed in the gritty 1980s East Village underground art scene, he eventually gained widespread recognition for his symbol-laden, surrealist-inspired paintings, collages, photographs, and videos. As the AIDS crisis deepened he became an outspoken activist, which led him to numerous clashes with the political and religious establishment. Raised a Catholic, Wojnarowicz channeled much of his anger toward the Church’s representatives, castigating them for their homophobia and indifference to the escalating toll of the AIDS epidemic.

His work often uses religious imagery in contexts that produced charges of sacrilege and blasphemy, such as when he created a video featuring a crucifix overrun with ants, and a painting depicting Jesus with a syringe in his arm. But in fact, Wojnarowicz separated genuine spirituality from official religion just as he separated what he called “the World” of authentic feeling and experience from the “pre-invented World” of the soul-destroying aspects of technology, science, language, law, and official history. His images of Christ highlight his identification with the suffering Jesus and serve as a rebuke to the modern world for deserting true Christian values.

Wojnarowicz’s works are complex and multilayered, resisting the simplistic interpretations laid on them by religious and political conservatives. The written texts merge sharply rendered social observations and vignettes about life on the street with dreamlike fantasies of escape, destruction, and sexual ecstasy. The paintings are similarly constructed from apparently disparate images. A single painting may combine torn bits of real maps or money, painted images from a repertoire that included cowboys, crumbling cities, prehistoric beasts, gay porn, and microscopic cells. In these works, flashes of beauty break through images of the devastation wrought by human action, while sexual desire and ecstasy are represented as manifestations of nature—havens of authentic feeling in a world that had become a mechanistic nightmare.

For Wojnarowicz, the Apocalypse had already come. Following the death of a close friend from AIDS, he wrote, “Hell is a place on earth. Heaven is a place in your head.” As the death toll soared and his own health deteriorated, his critiques became ever more pointed and his clashes with the establishment ever sharper. He succumbed to complications from AIDS in 1992 at age 37.

As these exhibitions suggest, the Apocalypse is ever malleable, a narrative that artists can recast to address specific problems and conditions. These artists provide a particularly American spin on the Apocalypse, reflecting the contradictory mix of hope and despair in which echoes of the founders’ conviction that America would be the “New Jerusalem” promised by the Book of Revelation mingle with a history of brutal conflicts cast by their protagonists as salvos in Revelation’s final battle of Good and Evil.

Conner, Shaw, Pettibon, and Wojnarowicz burrow into moments in America’s recent past when the forces of darkness seemed ascendant. Conner’s reflections on the allure of nuclear annihilation during the Cold War, Shaw’s fascination with religious sects that resist the pull of modernity, Pettibon’s exploration of the rubble left by the failure of the 1960s utopian dreams, and Wojnarowicz’s evocation of the AIDS catastrophe of the 1980s all belong to a tradition of anxiety rooted in Apocalyptic thinking. But they also remind us of the ambiguity at the heart of the eschatological narrative. The End looms, but there remains a large space for human agency. A sense of doom may be eternal. What matters is what we do about it.

A version of this story originally appeared in the Fall 2017 issue of ARTnews on page 110 under the title “The Four Horsemen of America’s Apocalypse.”