BY SURA WOOD

A retrospective has the ability to map the arc of an artist's career, its unifying and diverging themes, but it's unlikely that it's an artist's intention to have his or her life's work shown en masse. So does this mode of presentation enhance, skew or alter the perception of the work? That question arose recently when viewing Bruce Conner: It's All True,the first and certainly most multi-faceted, comprehensive survey of the prodigious 60-year output of this Bay Area iconoclast who, to paraphrase that old Sinatra standard, did it his way. While many visitors will have a passing familiarity with Conner's work and have been exposed to it in small doses over the years, immersion in a large, concentrated volume in one sitting yields a far grimmer impression of his oeuvre. Best-known for his assemblages whose materials he scavenged from the streets and thrift shops of his Western Addition neighborhood, his fluency in multiple mediums is borne out by the over 300 photograms, photographs, videos, sculptures, drawings, early paintings and engraving collages here, as well as 10 of his influential experimental films, which are integrated, as he would have wished, into the context of the massive show. Chock-full of artworks, and inclusive almost to its detriment, the exhibition could have done with some pruning. Plan to spend the better part of a stimulating afternoon taking it all in.

Bruce Conner, "The Artist" (1990), collage of found illustrations; collection of Joel Wachs. Photo: Conner Family Trust, SF/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

The show, which was organized by SFMOMA and opened at MOMA in New York last summer, is an intense affair, a walk on the dark side with a mischievous provocateur of the first order. Conner even ran for San Francisco Supervisor, recruiting an unsuspecting elephant for a campaign flyer. He came of age, artistically speaking, in the mid-1960s, the decade that never lets go, and he lived a creative life in the shadow of the very real prospect of nuclear annihilation following the Allied bombing of Japan and ensuing flurry of nuclear tests. "BOMBHEAD" (1989), a collaged found illustration and photocopy depicting a man in shirt and tie who has a mushroom cloud where his head should be, seems like a cheeky though ominous tip of the black derby to Magritte. But "Crossroads" (1976), a riveting, 37-minute black & white 35mm film (transferred to video) of two initial nuclear weapons tests conducted at Bikini Atoll in 1946, is deadly serious. The amalgamation of found footage shot by over 700 cameras, from different angles and at multiple slow-motion speeds, captures the awesome explosions. Horrifying in their magnitude and the sheer power of their destructive force, they're hard to look at, impossible to turn away from, and terribly sad. The film, amplified by soundtracks commissioned by Conner from Patrick Gleeson and Terry Riley, is screened in a hushed booth.

Drawing and film remained constants in Conner's career, as did his habit of thinking outside the box, as he did with "Angels" (1973-75), a series of 29 tall, rectangular, uniformly-sized photograms made with projected light and photosensitive paper. Conner stood on a platform blocking some or all of the light, producing spectral gamma-ray images, some suggesting aliens with white-gloved hands; together, they form a Greek chorus from the Great Beyond. They're displayed as they were when first shown at a dimly lit, blackened gallery in 1986, minus the box of crickets Conner had installed for atmospherics.

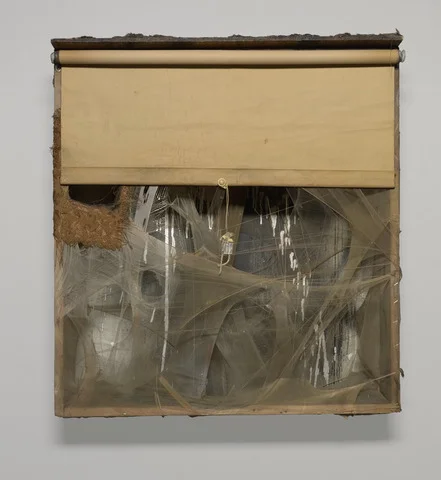

Bruce Conner, "Spider Lady Nest" (1959), wood box with aluminum paint, spray paint, window shade, nylon, thread, fabric, fur, lead customs seal on string, pearl bead, cotton ball, feathers, tassels, and cardboard. Yale University Art Gallery. Photo: Conner Family Trust, SF/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Emerging full-blown as if from the head of Zeus with a voice difficult to ignore, Conner arrived on the scene in earnest with "Child" (1959), a gruesome, cracked-black-wax likeness of an infant with partially amputated legs. Strapped to a wooden high chair, its contorted face is frozen in a permanent howl of terror. The notorious work, a protest against the death penalty, in particular the pending execution of convicted Los Angeles rapist and kidnapper Caryl Chessman, slowly disintegrated and has been reconstructed by NYMOMA's conservation team. It's shown in a gallery of the macabre with the understated title Dark Sculptures (1959-63), along with other grotesque, undeniably magnetizing assemblages that could be production designs for a haunted-house horror movie. Just in time for Halloween, there's "Cherub" (1959), in which a doll's head presses against a nylon scrim, and "Couch" (1963), a skull with a hole in its eye-socket, wrapped in cloth that's tied by rope at the neck, lying inert on a moldy antique divan.

Though a ray of sunshine penetrated the gloom during his brief stint in Mexico (1961-62), an obsession with decay and the withering effects of time, informed by the possibility of extinction and Cold War dread, permeates much of his work, as does a preoccupation with spider webs and ladies' hosiery, materials that are creepy and sexy, respectively, and as a bonus, can veil and obscure. There's an aura of Victorian haute past its prime in "The Bride" (1960), a small-scale construction of a dilapidated mansion that could have belonged to Miss Havisham in Charles Dickens' Great Expectations. Abandoned and swathed in cobwebs, it contains secrets unearthed by none but the brave.

Occupying several galleries, the assemblages are the spine of the show, and one can spend delicious hours lost in their charms. Though a channel for his originality and a medium at which he clearly excelled, by the time he received acclaim for them, he had moved on, one of several drastic shifts he made in his career, including declaring himself dead at one point.

Conner created his final assemblage in 1964. "Looking Glass," a biting critique of voyeurism and consumption of female sexuality, features a chunk of dried blowfish with mannequin arms and painted fingernails caught in nylon netting. Sitting on the top shelf of an open cabinet, it's like a madam presiding over a bawdy house whose walls are papered with nudie girlie pictures. One half-expects to be socked with the scent of cheap perfume.