Marilyn Times Five (1973 USA 12 mins)

Filmmaker: Bruce Conner

Mus: “I’m Through with Love”, words and music by Matty Malneck, Gus Kahn, Jerry Livingston, sung by Marilyn Monroe

BY HOLLY WILLIS

Bruce Conner’s film career began explosively in 1958 with the release of a 12-minute black-and-white film simply titled A Movie, composed exclusively of found footage material. What made the film an iconographic component of American avant-garde cinema was Conner’s exquisite editing and his ability to craft a moving image artwork that was at once an incisive, if elusive, critique of American pomposity and a profound meditation on visual rhythms and textures. Conner went on to create an inimical body of work that includes more than 20 remarkable avant-garde films before his death in 2008, and his acute critical eye contributed to a larger fascination with media-based analysis that continues to thrive today.

A decade and a half after A Movie, Conner released Marilyn Times Five, a work that continues the filmmaker’s earlier obsession both with found footage and cinematic rhythm, but adds to it a study of image structure and form. Indeed, whereas A Movie explores the capacious potential of restructured narrative through the orchestration and suggested continuity among innumerable and often disparate moving image sequences, Marilyn Times Five centres on a single short sequence, studying it with an exacting eye over and over until it yields new meanings.

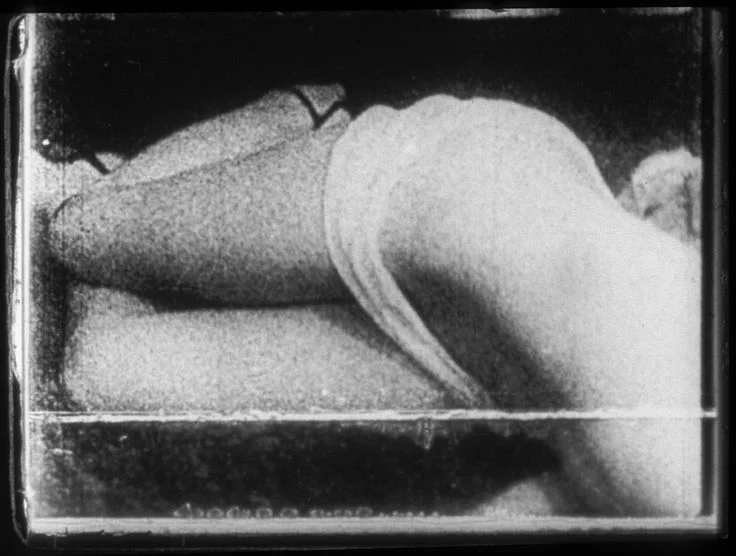

The short snippet of footage that forms the film’s basic “raw” material shows a woman who is nude, with the exception of underwear, in various poses; structured in five sections around the repetition of the song “I’m Through With Love”, the film continuously explores aspects of the image sequence, cutting and re-cutting it into myriad, almost dizzying permutations. Conner also uses bits of black leader to punctuate the film, withholding the image and, as a result, augmenting our own awareness of the desire to see. Throughout the five segments, Conner by turns eroticises the woman’s body with a caressing eye, twists it into uncomfortable poses with zesty humour, and ultimately suggests that the body’s objectification is deeply troubling, all through the careful cutting and rearranging of shots.

The film gains additional momentum with respect to its reputed subject, who is referenced in the title, namely Marilyn Monroe; viewers are led to believe that the woman in the film is indeed the famous actress. With this aspect of the project, Conner critiques the pernicious curiosity and voyeurism that subtends our viewing of the woman’s body; and once again, Conner elegantly leads us through the pleasures of looking, followed by an awareness and reflection on that pleasure. Through repetition, we are brought full circle from buoyant engagement to critical awareness.

That the woman may not be Monroe haunts the film in fascinating ways. Does it matter who the woman is? What value is gained in the film, and in our viewing, if it is Monroe? And what is lost if it isn’t? Several writers claim that the woman is actually Arline Hunter, an actress and model who closely resembled Monroe. When film scholar Scott MacDonald spoke with Conner in 1981 for an interview later collected in the first volume of A Critical Cinema, he asked if the woman in the film was Monroe; Conner had a fitting answer: “I tell people that while it may or may not have been Marilyn Monroe in the original footage, it’s her now” (1). He goes on to add: “Part of what the film is about is the roles people play, and I think it fits either way. It’s her image and her persona.”

In describing the film’s broader context, some critics portray Marilyn Times Five as a structuralist film, noting that its attention to film form contributes to the larger structuralist project of examining the fundamental properties and materials of cinema. However, while Marilyn Times Five certainly shares certain qualities with other stucturalist films – its focus on editing, duration and repetition, for example – overall, the film’s perspicacious assessment of the thematic elements of the film –specifically gender, voyeurism and celebrity – really make it part of different meta-critical genre of experimental filmmaking.

If Conner’s ability to mobilise a kind of meta-critique characterises his work in one sense, the other half of that critical stance is Conner’s obvious love of cinema and moving images. He often complained about television and its overt and assaultive manipulation, and his work countered that often mindless manipulation with aplomb. In his introduction to the interview with Conner, MacDonald notes,

But whatever the subject or the mood of particular films, the driving force in Conner’s work seems to me to be an ecstasy that is generated by his being able to recycle even the most banal commercial and industrial film imagery into new works that are not only dense and sophisticated but also accessible to almost any viewer. (2)

Conner’s body of work remains a unique and highly influential component of the American avant-garde, and Marilyn Times Five, with its loops, use of music and ability to combine a critical analysis as part of its very form, remains a powerful example of cinema’s potential.

Endnotes

- Scott MacDonald, A Critical Cinema: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1988, p. 253.

- MacDonald, pp. 244-45.