BY EMILY SHARPE

The haunting work titled CHILD goes on show in New York after two decades away from the public eye.

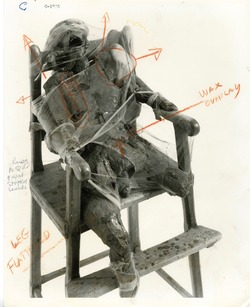

Conservators at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York have done the seemingly impossible: they have brought Bruce Conner’s CHILD (1959-60), a haunting sculpture of a gas chamber execution, back from the dead ahead of a major travelling exhibition.

Conner (1933-2008) made the work, a black-wax figure of a boy—its head thrown back and mouth open as if screaming—covered with nylon webbing and strapped to a high-chair, in response to the planned execution of career criminal Caryl Chessman. In 1948, Chessman was sentenced to die in the gas chamber for kidnapping—a crime punishable by death in California at the time. Although the severity of his sentence for a non-lethal crime divided public opinion, he was eventually executed in 1960 after several widely publicised attempts to overturn his conviction.

The US artist originally wanted to cast the work in bronze (and encase it in glass so it would look like a gas chamber) but eventually settled on sculpting it from casting wax on which he poured hot wax. It sits in a child’s chair once owned by the Abstract Expressionist Sonia Gechtoff, who was “horrified when she learned it was used in this piece”, says Roger Griffith, MoMA’s associate sculpture conservator. The figure is covered in nylon webbing, in keeping with the artist’s interest in the macabre early in his career. “He wanted objects to look old and to create a sense of revulsion and pain,” says Laura Hoptman, the museum’s painting and sculpture curator. She has co-curated a major survey of Conner’s work with colleagues from MoMA and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art--the organiser of the show. It will travel to San Francisco after its New York debut in July.

Whitney no-show

When it entered MoMA’s collection in 1970, CHILD was in a deteriorated state and so has never been exhibited there. In fact, the piece has not been on public display since 1995, when it was pulled from a show at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York at Conner’s request. The slouched figure that confronted the artist at the Whitney more than two decades ago was a far cry from Conner’s original creation. Among other things, its head had collapsed onto its chest—a change that drastically altered the meaning of the piece. “CHILD was intended to show pain at the moment of execution and, over the years, its head had slumped so it looked dead,” Hoptman says.

Following CHILD’s return to MoMA in 1995, conservators made several attempts to restore the piece, and sought Conner’s advice on its original appearance and the materials used in its creation. Unfortunately, these attempts failed. It was brought out of storage again in 2014, six years after the artist’s death, when conservators, curators and representatives from the Conner Family Trust came together to discuss the work. It was decided that CHILD deserved another shot at life.

Nylons not pantyhose

The only way to treat CHILD was to take it apart. A key part of the process involved constructing an internal armature, which the figure lacked and led to its head falling on its collapsed chest. Before Conner died, he accepted that certain additions were needed to restore the piece to its 1960 appearance. The support is made out of sheets of polycaprolactone, a thermoplastic polyester resin once used in the medical industry and now embraced by artists such as Matthew Barney, who uses a different form of it to create his pour pieces. This is MoMA’s first experience with the material and conservation fellow Megan Randall says its benefits include being “endlessly reheatable so it can be bent over and over to adjust the shape as needed”.

Reassembling the figure into the correct position in its chair was one of the biggest challenges. “We didn’t know how far he had shifted until we began to reassemble it,” Griffith says. But, Randall says, “the margins of error are very small because he only fits in the chair a certain way.” The wax itself was in good condition. “It’s an incredibly durable material,” says MoMA’s chief conservator James Coddington, noting that it was used by ancient Egyptian artisans. “It had not lost its substance, just its shape.”

Over the years, many of the work’s original nylons had been removed so vintage ones—not pantyhose, as Conner was very specific about his choice of hosiery—were sourced from what has become many conservators’ go-to retail source: eBay. “We often find we’re bidding against colleagues,” Coddington says. But the nylons that had remained were in remarkably good condition. “They’re more robust than we had thought,” he says, adding that he wouldn’t have a problem with CHILD being on view for extended periods.

In the end, Griffith estimates that, aside from the internal armature, the restored piece only contains between 1% and 2% of non-original materials. “We were confident it could be [successfully treated] because the material was all there,” Griffith says. Coddington was more sceptical. “History had come to ask if this object existed any more,” he says. “Megan and Roger were confident; I was the counter voice.”

“Rarely in your career as a conservator do you get a chance to bring a work back to life,” Griffith says. “I’m pleased the curators had the confidence in us to let us do it.”

Bruce Conner: It’s All True, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 3 July-2 October; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 29 October-22 January 2017